|

|

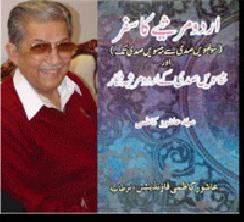

| Syed Ashoor kazmi |

A tribute to Marsiya writers

By Intizar Husain

Urdu Marsiya for some time seems to have come in the focus of researcher’s attention. Perhaps it all started with the

death centenary of Mir Anis in 1974 when the scholars once again turned to this giant Marsiya writer. Urdu Marsiya for some time seems to have come in the focus of researcher’s attention. Perhaps it all started with the

death centenary of Mir Anis in 1974 when the scholars once again turned to this giant Marsiya writer.

With the advent

of the present century came his second birth centenary, which provided a new incentive to his researchers and critics. And

while talking of Anis one feels compelled to refer to his senior rival Mirza Dabir. This led to a revival of interest in Dabir

as well as in the tradition of Urdu Marsiya. So in recent decades a number of research works have come out with reference

to Anis, Dabir, and the Marsiya tradition at large.

The latest is Syed Ashoor Kazmi’s stupendous work under the

title Urdu Marsiye ka Safar. This voluminous book running in more than twelve hundred pages has been published by England’s

Ashoor Kazmi Foundation in cooperation with India’s Educational Publishing House, which has published it from Delhi.

Here we see Urdu Marsiya being born in Deccan in times of Quli Qutab Shah and Ali Adil Shah. Later we see it travelling from

Deccan to Delhi, and from Delhi to Lucknow where it finds its culmination in the poetic genius of Anis. Soon after it, this

poetic form solely devoted to the depiction of the tragedy of Karbala enters in the 20th century.

Now it is a wide

ranging journey taking different regions of the subcontinent in its fold. With its entry in Pakistan it earns a new lease

of life at the hands of the newly-emerged Marsiya writers, who in their enthusiasm for this form claim to have founded a new

Marsiya tradition calling it modern Marsiya.

This journey, began in the mid 16th century, has now entered in the 21st

century and seems betraying no sign of exhaustion. With the exception of ghazal, no other poetic form in Urdu has shown the

tenacity to endure the ravages of time for so long and remain alive. Of course, it constantly drew sustenance from the ritual

of majlis, but, at the same time, it in the hands of creatively alive writers showed the capability to cross the limits of

this ritual and assert on the literary level.

Ashoor Kazmi has traced this journey with particular reference to its

passage during the 20th century in a way that it can be taken as a history of Urdu Marsiya. But this history is mainly the

history of the Marsiya during the 20th century as represented by the Marsiya writers appearing during this period. The Marsiya

history ending on the termination of the 19th century is in a fact a brief survey of the period beginning with Quli Qutab

Shah in the mid 16th century and ending at the close of the 19th century with Mir Nafees forming a bridge between the dying

century and the one newly born.

But the bridge is itself at its end. How strange that the journey of the 20th century

Marsiya is headed in this account by Mir Nafees. Ashoor Kazmi treats him as the first Marsiya writer of the 20th century while

he lived only for two months after the end of the 19th century. Mir Nafees died, as recorded by Zamir Akhtar Naqvi, on March

2, 1901. So that makes him the last Marsiya writer of the 19th century.

In fact the value of his research lies in his

tracing out the Marsiya writers, known as well as unknown, from every corner of the subcontinent. As for the Marsiya writers

belonging to the later category, their number knows no limit. So the lucky ones finding place in this volume owe their inclusion

to a random choice.

We see here a large number of Marsiya writers coming from different regions of India and Pakistan.

Gathered together they make a crowd, which asks for some kind of categorization. Ashoor Kazmi does make such an attempt by

calling each category a dabistan. But what is the basis of this categorization? For instance, does Karachi’s Marsiya

carry with it something different from what we find in Marsiyas written in Punjab? If not, why should the two be treated as

separate dabistans? Perhaps the compiler himself is not sure about any such differentiation. And so this categorization ends

in confusion.

However, at least two categories, one enlisting Hindu Marsiya writers and the other comprising female

Marsiya writers, are valid. The former one shows the poets belonging to another faith, the dominant faith of India, participating

in the tradition of Urdu Marsiya and making its contribution to it. And it needs to be noted that this participation originated

not from Lucknow but from Benaras when it was under the rule of Hindu rajas. In fact a raja from among them Raja Balwan Singh,

the ruler of Benaras, was the first from among the Hindus, who, according to the information provided by Ashoor Kazmi, attempted

to write a Marsiya.

Kazmi’s list includes a number of Hindu Marsiya writers such as Gopi Nath Aman, Kalidas Gupta

Raza, and most of all Dalloo Ram Kausari, whose one rubai was at one time among the most popular couplets of Marsiya. As for

Roop Kumari, she stands distinguished among Hindu Marsiya writers because of her Marsiya expression being steeped in the cultural

tradition she had inherited from her faith.

The other category bringing with it a long list of female Marsiya writers

has a significance of its own. It is evident from this list that females’ creative genius in our society found its poetic

expression more through Marsiya than through any other form of poetry. Because of restrictions imposed by our social order,

it could hardly find its expression in ghazal. It found its outlet in the form of Marsiya.

|